The Warmth Of Space

By Alyssa Eakman

It’s easy to forget how much humanity is in science.

Imagining science, especially on a professional level, may evoke mental images of metal instruments, white lab coats, and cold, hard calculations. Robots and screens and beakers are part of science, of course, but what often gets overlooked is humanity.

Behind all the overworked computers and lines of code and chalkboard mathematics are humans.

The curiosity and cravings for company that are so innate to human nature underscore every advancement we make in science. Space exploration may be one of the best examples of how the warmth of humanity is built into every wire and piece of metal that we send out into the universe. At the core of the search for life on other planets — that hope of discovering something familiar even on worlds and in galaxies far away — is our own psychological need for companionship.

Humans are social animals. Throughout our lives, we seek out connections with others and build communities out of hobbies, identities, proximity, and other factors. Often, we crave companions to sit with at meals and want to find others to share in our interests. Social connection is one of the most important needs a human must meet (Seppala). This concept transcends our individual selves and can even be applied to our species as a whole. The human race does not want to be alone in the universe, and so we reach out again, and again, and again.

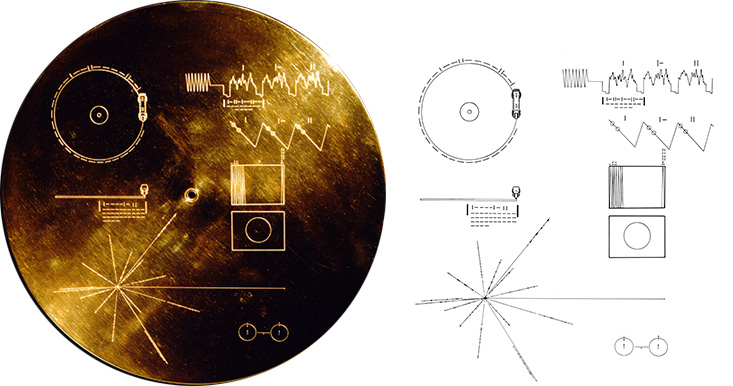

Perhaps our grandest call sent thus far into the void came in the form of the Voyager Golden Records. These records were placed aboard both the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft to be cast out into interstellar space like a message in a bottle being tossed into an ocean with no end in sight.

The record was filled with little gifts and treasures of humanity mixed with samples of our natural planet. Sounds of the ocean, wind, and thunder were added along with audio of human footsteps and laughter. Music from all different cultures and time periods and greetings spoken in 55 ancient and modern languages were sent out into the universe. 115 images including instructions on how to play the record, sheets of music, skyscrapers, chemical definitions, and depictions of the Earth and other planets in our solar system were burned into the disc.

Though there are slim odds of the contents of this record being comprehensible to anyone that may find it, if that day should come, the Voyager Golden Record reflects what we as humans treasure about ourselves. When humanity set out to put together something that describes us as a species, something that we hope might one day reach an alien civilization, we chose children’s laughter and animal songs and the brainwaves of a person thinking about what it’s like to fall in love.

44 years after launch, Voyager 1 is over 14.1 billion miles away from Earth, well into interstellar space. It will take about 40,000 years for the spacecraft to reach the star Gliese 445 in the Camelopardalis constellation. Science is a vessel for a hope that is very human, and the spirit of humanity is reflected in how we choose to use our technology.

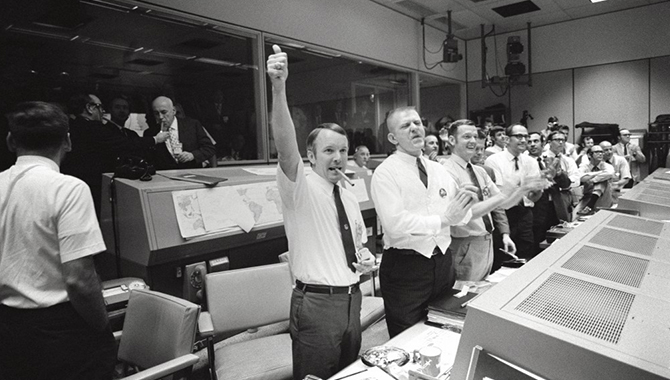

Human nature also bleeds through in the way we bond with the machines we use to chase our highest hopes. One of the fondest memories of the Curiosity rover involves its first anniversary on Mars. Scientists at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center commemorated the occasion by ‘singing’ Happy Birthday to Curiosity. The rover contained a soil sample analysis unit that emitted a range of frequencies. Using the different noises Curiosity could produce, the scientists were able to take a few minutes from their strict schedules and put together a little song in celebration (see references).

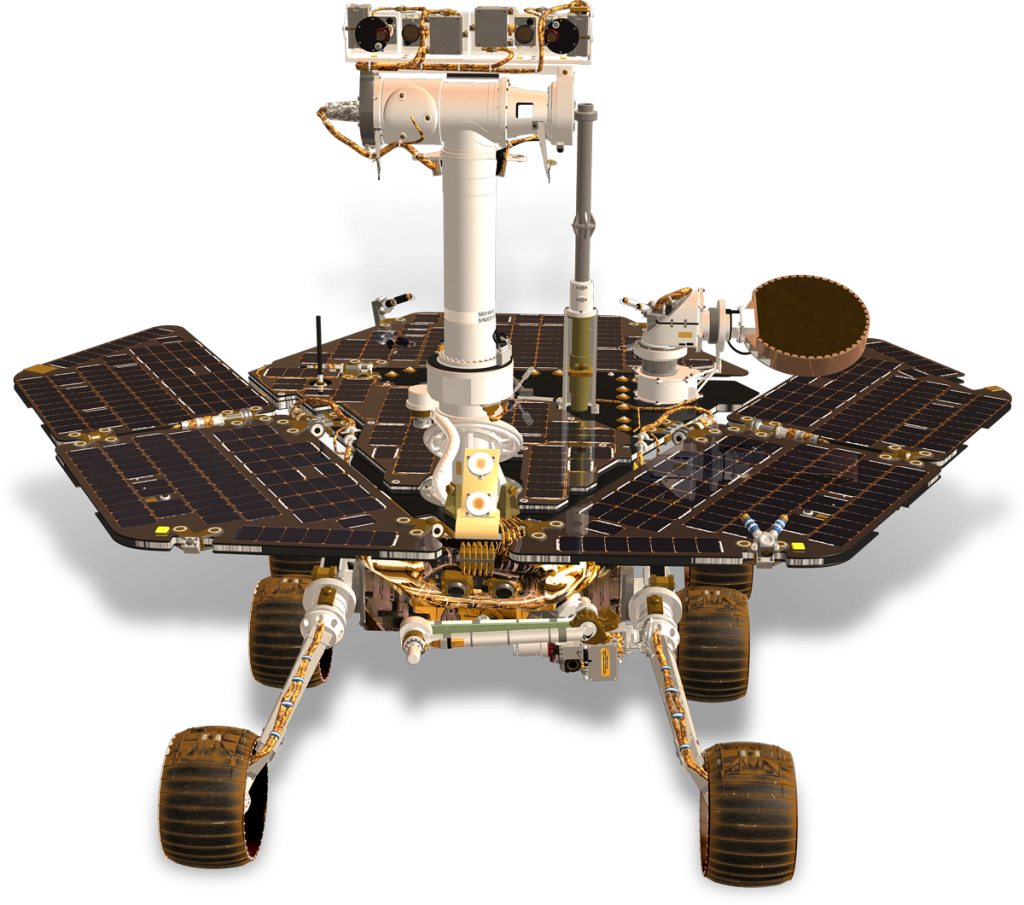

There are obviously practical reasons to name rovers and missions, but like with many parts of science, it often reflects how humans interact with what we create. The Opportunity rover quickly gained the affectionate nickname “Oppy”, both by scientists and by the public.

We feel a sense of attachment to the objects that serve a purpose in our life. In the same way that a child may cheer on a toy boat racing down a river, the general public developed a soft spot for Oppy — the brave little robot venturing out into the harsh unknown in service of our own goals. When contact was lost with Oppy after a major dust storm, the scientists behind the mission mourned along with the world.

Engineers would often play wake-up songs to the rover whenever it went inactive. The team began to develop an attachment to Oppy through these routines. When the rover lost communication with Earth, individual team members all set out to wake Oppy up. For eight months they persisted, playing loud, upbeat songs in hopes of pushing the rover into alertness, but nothing worked. Eventually, the team sang Oppy one final song: I’ll Be Seeing You by Billie Holiday. The song was chosen for the fondness and gratitude woven through lyrics of loss and yearning:

I’ll find you in the morning sun

I’ll Be Seeing You, by Billie Holiday

And when the night is new

I’ll be looking at the moon

But I’ll be seeing you

Though it’s an appropriately sad song for a farewell to a rover that had given so much for us, it also touches on the bittersweet concept of living on. Oppy will always be remembered in the scientific discoveries it gave us and the advancements we were able to build from them.

Opportunity embodied the ambitions of humanity. The little rover was only built for a 90 day mission, but exceeded all expectations and lived for 15 years on Mars. We like to root for an underdog, and so we took pride in Oppy’s unexpected perseverance, projecting our own hopes and dreams across the cosmos. The rover’s final transmission was, roughly translated from the data, “My battery is low and it’s getting dark.” Realistically, we know it’s a piece of machinery that cannot feel pain or fear. Yet, these final words, a frightening vision of the end, evoke a very real feeling of empathy from us.

Humans form such affectionate bonds with objects even on smaller scales. We have always talked about cars and boats like they are people, but the effect is even more pronounced when it comes to household technology like Roombas. Many people view these robots as partners, companions, and even members of the family.

One study targeting the intimacy between humans and domestic robots found that people tend to anthropomorphize, which involves assigning human-like qualities to a nonhuman thing. The interviewed Roomba owners often perceived their robots to have unique personalities and intentions, even going as far to give them names, genders, and ages. By observing patterns in the robot’s random navigation, such as the Roomba constantly getting stuck in one area, participants felt that their robots were more lifelike compared to the average machine that is thought to be precise and perfect. Humans are adept at detecting habits and patterns, leading us to build personalities for these unfeeling robots.

Participants also described genuine feelings of distress at having to exchange their Roombas or send them in for repairs, as if the robots were ‘sick’ or ‘injured’. The majority of the participants in the study also claimed that they had adjusted their houses to fit the Roomba, even tidying up in advance so the robot has an easier time navigating or has less to clean (Sung et al., 2007). Humans already tend to anthropomorphize our living, breathing, pets, but this effect is even more pronounced on these little household helpers that, in reality, aren’t much more than programmed pieces of metal. They genuinely grow to become valued members of the family.

An fMRI study examining how humans interact with robots showed participants videos of a human, a robot, and a different inanimate object being treated in either violent or affectionate ways. Similar neural patterns in the limbic system of the brain were detected in participants viewing both the human and the robot being treated poorly, demonstrating that humans felt empathy for robots in similar ways to how we feel emotions for other people (Rosenthal-von der Pütten et al., 2013). People even hesitate when asked to hit a robot with a mallet, expressing worry that the robot will feel the pain, and bomb-disposal robots in the military have been given funerals and unofficial medals of honor (Riddoch & Cross, 2021; Nyholm & Smids, 2020).

These are very real, very human bonds that we form with technology, even the devices we don’t create ourselves. It’s no wonder that we grow to love the machines we send out to other worlds and the time capsules we desperately hope will reach someone, someday. Some people even feel a sense of injustice from the scientific reclassification of Pluto as a dwarf planet, despite it having no impact on our daily lives.

Science can be cold metal and wires and logic and lines of code. Technical advancements are certainly no small part of the field. But we still mustn’t forget the human drive behind all of these things. Science can also be the sounds of laughter on a golden record flying through space, singing songs to a rover 245 million miles away, and fervently apologizing to your Roomba when you collide in the middle of the kitchen.

Space might be cold, but the affectionate tendencies of human nature will always lend an element of warmth.

References

- Lonely Curiosity rover sings ‘Happy Birthday’ to itself on Mars. Washington Post.

- Happy Birthday Curiosity! | Mars Video

- Mars Exploration Rovers

- Nyholm, S., & Smids, J. (2020). Can a Robot Be a Good Colleague? Science and Engineering Ethics, 26(4), 2169–2188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00172-6

- Riddoch, K. A., & Cross, Emily. S. (2021). “Hit the Robot on the Head With This Mallet” – Making a Case for Including More Open Questions in HRI Research. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2021.603510

- Rosenthal-von der Pütten, A. M., Schulte, F. P., Eimler, S. C., Hoffmann, L., Sobieraj, S., Maderwald, S., Krämer, N. C., & Brand, M. (2013). Neural correlates of empathy towards robots. 2013 8th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), 215–216. https://doi.org/10.1109/HRI.2013.6483578

- Seppala, E. Social Connection and Compassion: Important Predictors of Health and Well-Being.

- NASA Said Goodbye to the Mars Rover with a Final Song. Los Angeles Magazine

- Sung, J.-Y., Guo, L., Grinter, R., & Christensen, H. (2007). “My Roomba Is Rambo”: Intimate Home Appliances. 4717. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74853-3_9

- Supporting Effective Teamwork at NASA | APPEL Knowledge Services

- Voyager 1, Wikipedia Entry

- Voyager Golden Record, Wikipedia Entry

- Voyager—Images on the Golden Record

- Voyager—Mission Status

- Voyager—The Golden Record Cover

Alyssa Eakman is a senior student at Tufts University in Massachusetts, double majoring in Astrophysics and Psychology and minoring in Dance. She is a BMSIS YSP research assistant working with Dr. Dimitra Atri on Martian subsurface habitability.