Beard-Seconds, Barns, and Other Unusual Units of Measurement

By Graham Lau (BMSIS Senior Research Investigator)

Units of measurement are essential tools for understanding and navigating our place in the universe. They give us frames of reference when communicating our ideas to each other—from simple ideas like how much flour to add for a bread recipe and how fast you’re allowed to drive without getting in trouble to more complex ideas like understanding the rate of expansion of the universe or calculating how much fuel a spacecraft needs to burn during a trajectory altering maneuver.

Imagine telling someone you have twelve of something, need to drive for three to reach a destination, or have sixteen to cut a wire on a bomb before disaster strikes. Without specifying units these statements are ambiguous and potentially misleading. Maybe you have twelve gold bricks or maybe you have twelve beans. Maybe your destination is three minutes away or three hours away. Having sixteen minutes to make a high pressure decision can be much different than only having sixteen seconds.

Scientific measurements rely on consistent and standardized units. Yet, throughout history, scientists and engineers have occasionally developed unusual and humorous units of measurement to better describe phenomena on wildly different scales.

Two such units—the beard-second and the barn—can illustrate how creativity in measurement can reveal both the vast and the minuscule features of the cosmos.

The Beard-Second: Measuring Time and Growth on a Microscopic Scale

Many of us working in the realms of Earth and space science have encountered light-years. A light-year (ly) is a unit of distance that measures how far light travels in a year in a vacuum in space. Given the vastness of the cosmos, having a distance measurement like light-years is necessary to put things into perspective and makes it far easier to understand cosmic distances. It’s a lot easier to envision the differences of the star Vega being ~25 ly away and the star Betelgeuse closer to 500 ly away than if we tried to understand those differences using units like meters (which is about 2.365×1017 m compared to 4.73×1018 m, for those who are interested).

Much like light-years, many units are created to be standardized and most useful in their very specific situations.

But sometimes scientists, engineers, and other scholars have created whimsical or bizarre units—sometimes just for fun but also sometimes just for the sake of showing unique connections.

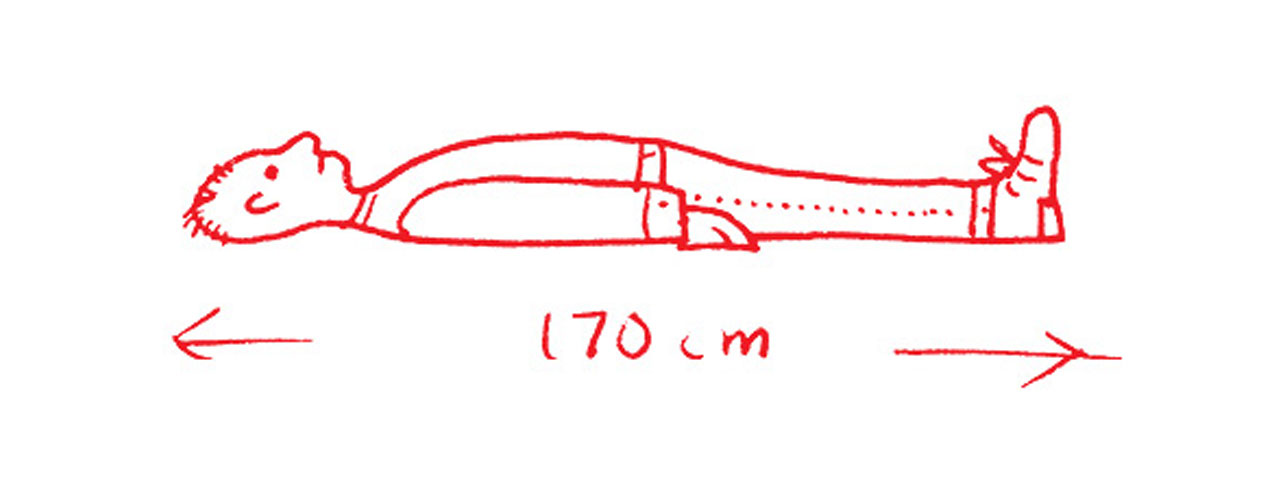

One famous example of a whimsical unit is the smoot, named after Oliver R. Smoot, an MIT student who, in 1958, served as a living measuring stick for the Harvard Bridge. The bridge was measured as 364.4 smoots plus an ear—a tradition still maintained by MIT students to this day. If you happen to visit Boston, you can go check it out for yourself! (Also, fun fact, Smoot himself later became the chairman of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) from 2001 to 2002 and president of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) from 2003 to 2004).

As this author is a hirsute individual, one of the other whimsical units of measurement that I also find fascinating is the beard-second.

Much as the light-year reflects the distance traveled by light in a vacuum in a year, the beard-second is a measurement of the estimated length of human hair grown in an average beard in one second.

Of course, not all human hair grows at the same rate, but for the sake of the measurement, this growth is estimated to be an average of 5 to 10 nanometers (nm) per second. For context, 1 nanometer is one-billionth of a meter—about the width of a few atoms lined up side by side. So a beard-second is a unit of distance that is slightly smaller than the width of the smallest viruses (which are about 20 nm).

Kemp Bennett Kolb proposed the beard-second as a unit of measurement in his book This Book Warps Space and Time. In his original estimate for the distance he used 10 nm as the distance. However, if you take a little time searching for the beard-second online, you’ll see a smattering of both 5 nm and 10 nm as the estimated distance.

For the sake of having some fun here, let’s use the 5 nm reference distance for a beard-second (that’s what Google and many online unit converters have decided to use). 5 nm, by the way, is also 0.000000005 m or 0.00000019685 inches (or 5.285×10-25 light-years).

One of my favorite distances to cover on my rowing machine is 5 km. It’s a fun standard distance that a lot of others who use rowing machines have timed themselves on, so it’s easier to have a large sample of times to know roughly how you’re doing. But what is 5 km in beard-seconds?

A little back of the envelope math (which is made even easier since the 5 from the km and the 5 from the nm will cancel out, making for some simple exponent math) will show that 5 km is the same as 1012 or 1 trillion beard-seconds.

Covering 1 trillion beard-seconds on a rowing machine for a short workout feels a bit surprisingly epic, albeit rather comical to consider.

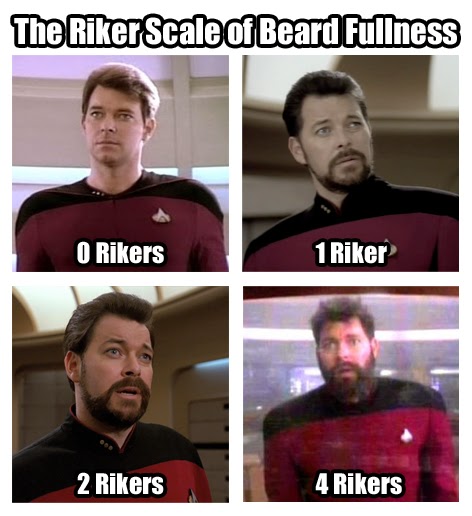

Like the lightyear the beard-second is a time-conditional unit of distance. However, while light’s speed in a vacuum is a fundamental constant of the universe, beard growth is subject to biological variance. Not everyone’s beard grows at the same rate, and environmental and genetic factors can alter growth patterns over time. To illustrate this variability, there’s even a humorous “Riker Scale,” named after the famously bearded Commander William Riker from Star Trek: The Next Generation. The scale rates the fullness of a beard and can be a playful reference point in the bearded trekkie community.

The Barn: A Physicist’s Measure of Precision

There are of course many other bizarre, silly, or whimsical units out there. Some of the silly sounding units are actually rather sensible units of measurement, but were given names based on comical comparisons to our other uses of language. Good examples are the banana equivalent dose (the amount of radiation exposure from eating an average banana), the Garn (named for an astronaut and serving as a NASA unit to measure sickness caused by space adaptation syndrome), and the barn.

The barn is a unit of area used in particle physics, where scientists often deal with unimaginably tiny cross-sections of atomic nuclei. First introduced in 1942 by researchers working on nuclear reactions, the barn was meant to simplify discussions of target areas in experiments. A barn is equal to 100 square femtometers (fm²), or 10⁻²⁸ square meters. For comparison, this area is roughly the size of a uranium nucleus.

The term “barn” originated as physicists joked that hitting a nucleus in a high-energy experiment was akin to “hitting the broad side of a barn”—a phrase usually used to describe poor aim. Ironically, the barn represents a cross-sectional area so minuscule that it underscores the difficulty of successfully striking such a target at the subatomic scale.

For a sense of scale, the screen area of an iPhone 14, measuring about 13.86 square inches, is equivalent to over 1.24 x 1027 barns—or 1.24 ronnabarns (the ronna- is the metric prefix for 1027). This staggering number highlights how vastly different scales of measurement are needed depending on the context.

Over time, physicists have extended the barn concept with smaller units like the outhouse (10⁻⁶ barns) and shed (10⁻²⁴ barns), further emphasizing their playful approach to precision.

Wikipedia maintains a detailed list of unusual measurements for a bit more exploration on some of the silly units we’ve created.

The Importance of Measurement Standards

While unusual units provide humor (and sometimes some insight), the global scientific community relies on the International System of Units (SI). SI simplifies communication across disciplines by using a base-10 system with standardized prefixes. Unfortunately, the United States continues to primarily use a customary unit system based on the old British Imperial System, which intermixes bases (e.g., inches, feet, and miles) leading to frequent unit conversion errors. Famously, a failed communication regarding unit conversion from the U.S. system to SI units by engineers is what caused the Mars Climate Orbiter to crash into Mars in 1999.

A fun illustration of the need to understand units can be seen in an episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.

The Season 9 episode titled “Mac and Dennis Buy a Timeshare” starts with Sweet Dee (played by Kaitlin Olsen) trying to sell some “wonder berries” to Charlie, Mac, and Dennis (played by Charlie Day, Rob McElhenny, and Glenn Howerton). Here’s how the intro scene goes down:

Dee: Charlie, allow me to demonstrate.

Charlie: Oh, you got a thing here.

Dee: Come over here and hold on to these. (She hands him two handles with cables attached to a device that might remind you of one of Scientology’s E-Meters). Now, this machine is gonna measure the level of toxins in your body caused by stress.

Charlie: All right. Where do I put my feet?

Dee: Wherever you want.

Charlie: I’m gonna put them on the stool.

Dee: Great. It doesn’t matter. Okay, here we go. (The device starts beeping) One twenty… One fourty… One fifty… seven?! Oh, shit, Charlie, 157?

Charlie: Is that bad?

Dee: Yeah, it’s not good.

Charlie: Guys, I got 157.

Dennis: Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. 157 what?

Dee: Units.

Charlie: Units, dude.

Dennis: Units of what?

Dee: Units of stress! You’re very, very high in your stress unit. But don’t even worry, because Invigaron can help you. These berries are chock-full of antioxidants and phytonutrients.

Charlie: Oh, thank God. All right, I’m sold. I’m in.

Mac: Of course you’re buying it, because you’re as big of an idiot as she is. You’re getting scammed, Dee.

Take home message: you can know about units or potentially get scammed…

Unusual units like the beard-second and barn serve as reminders of the ingenuity and humor that science can inspire.

They offer a fresh perspective on measurement, encouraging curiosity about the often hidden scales of reality. Whether you’re calculating beard growth or contemplating the nucleus of an atom, understanding units brings us closer to a shared understanding of the universe.

So, next time someone mentions a unit you’ve never heard of, ask them to explain—and perhaps you’ll discover a whole new way of measuring the world. If you happen to find yourself on an engineering team building a spacecraft for Mars, make sure you know which unit systems and conversions are being used. And make sure no one tries to scam you by making bold claims without sharing their sources and units of measurement.

About the Author: Dr. Graham Lau is an astrobiologist and communicator of science. He serves as the Director of Communications and Marketing for Blue Marble Space, as a Senior Research Investigator with BMSIS, and as the Host of the NASA-funded show “Ask an Astrobiologist”. This writing comes from a reworked version of an earlier article published in A Cosmobiologist’s Dream in 2015.

For further posts and ideas from BMSIS, check out our LinkedIn company page or subscribe to our monthly newsletter, the BMS Insider.