Ecosystems in Space Habitats

By Luke Concollato

People have been observing how ecosystems function since humans first began hunting. When our primitive ancestors began cultivating land they embarked on a journey to work with nature. This journey continues today as modern ecologists unravel nature’s complex relationships.

Ecologists invented a way to quantify how nature contributes to our quality of life with a concept called “ecosystem services.” Ecosystem services have been developed to describe the various ways nature benefits our lives. Ecosystem services are divided into four categories; provisional, regulating, supporting and cultural. Understanding ecosystem services is essential to understanding modern ideas such as sustainability, but it does not stop there. Our ambitions to travel beyond Earth offer the ultimate test, where there is no biosphere to take for granted.

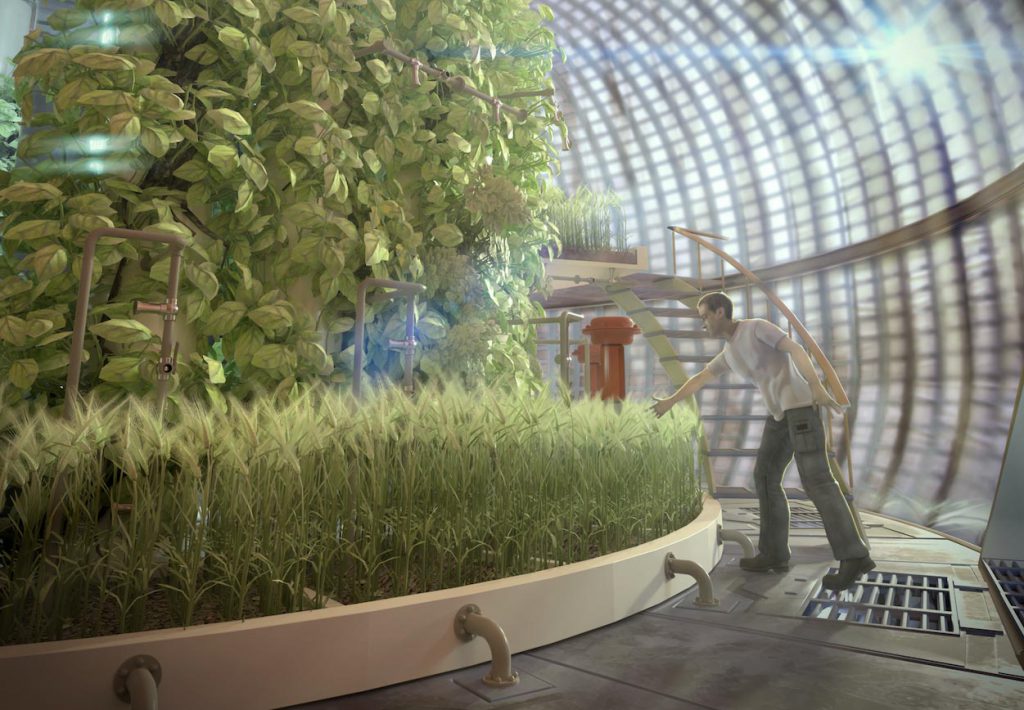

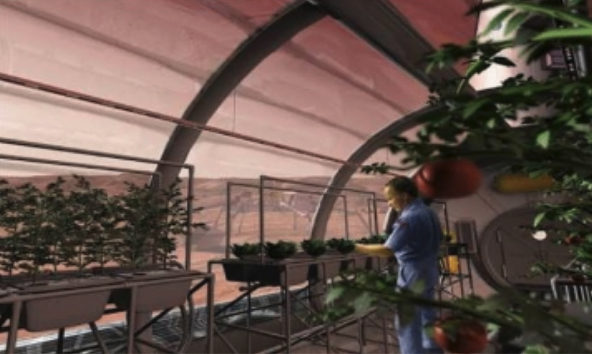

Designing space habitats that are capable of producing food and recycling waste will be critical for future missions. An interplanetary habitat will be a complex environment which can be modelled after how ecologists understand nature. We can use ecosystem services thinking to identify the benefits a habitat provides to astronauts.

Lets first look at provisional ecosystem services – those that directly provide something. For self-sufficient habitats, this could be food from crop production. The International Space Station has plant growth chambers that produce certain types of crops to supplement astronaut diets. Given that cost and logistics will prevent easily resupplying prepared food on longer missions, growing crops will be a crucial component of a sustainable habitat.

Regulating ecosystem services help to regulate the surrounding environment. The Earth regulates its atmosphere through complex nutrient cycles like the carbon and nitrogen cycles. A closed habitat in space will need to rely on technology to imitate this, but plants can convert carbon dioxide into oxygen through photosynthesis. Relying purely on plants to maintain the atmosphere in a closed habitat is extremely risky, however, plants can supplement the current methods of carbon dioxide removal to improve energy usage.

Supporting ecosystem services indirectly benefit the astronauts onboard. For example, one problem Martian farmers will encounter is the high concentration of toxins in Martian regolith – the rocky material on the surface. Phytoremediation, the process of removing toxic compounds from soil using plants, is a technique that environmental engineers have used to restore contaminated land on Earth. In a similar manner, plants and even some bacteria, may be able to detoxify Martian regolith, allowing crops to be grown safely.

Finally, the cultural ecosystem services provide psychological benefits to astronauts. Astronauts have reported that tending to plants during missions is an enjoyable activity. This psychological benefit could be at risk from overly eager engineers on a crusade to automate everything. Engineers must find the balance between automating undesirable tasks and allowing the crew to benefit from doing the work themselves.

Our ancestors ventured to new lands and were sustained by their ability to grow crops and farm. Modern explorers taking on the solar system will have to master growing plants in space on their starward voyage – for food production, atmospheric regulation, and happiness. What a lonely venture into the cosmos it would be without the very thing that gives us life back home.

Having graduated from Physics at Oxford University, Luke now works as a software developer with a keen interest in ecology and ecosystem modeling. Luke is also developing a web platform for plants in space with BMSIS.